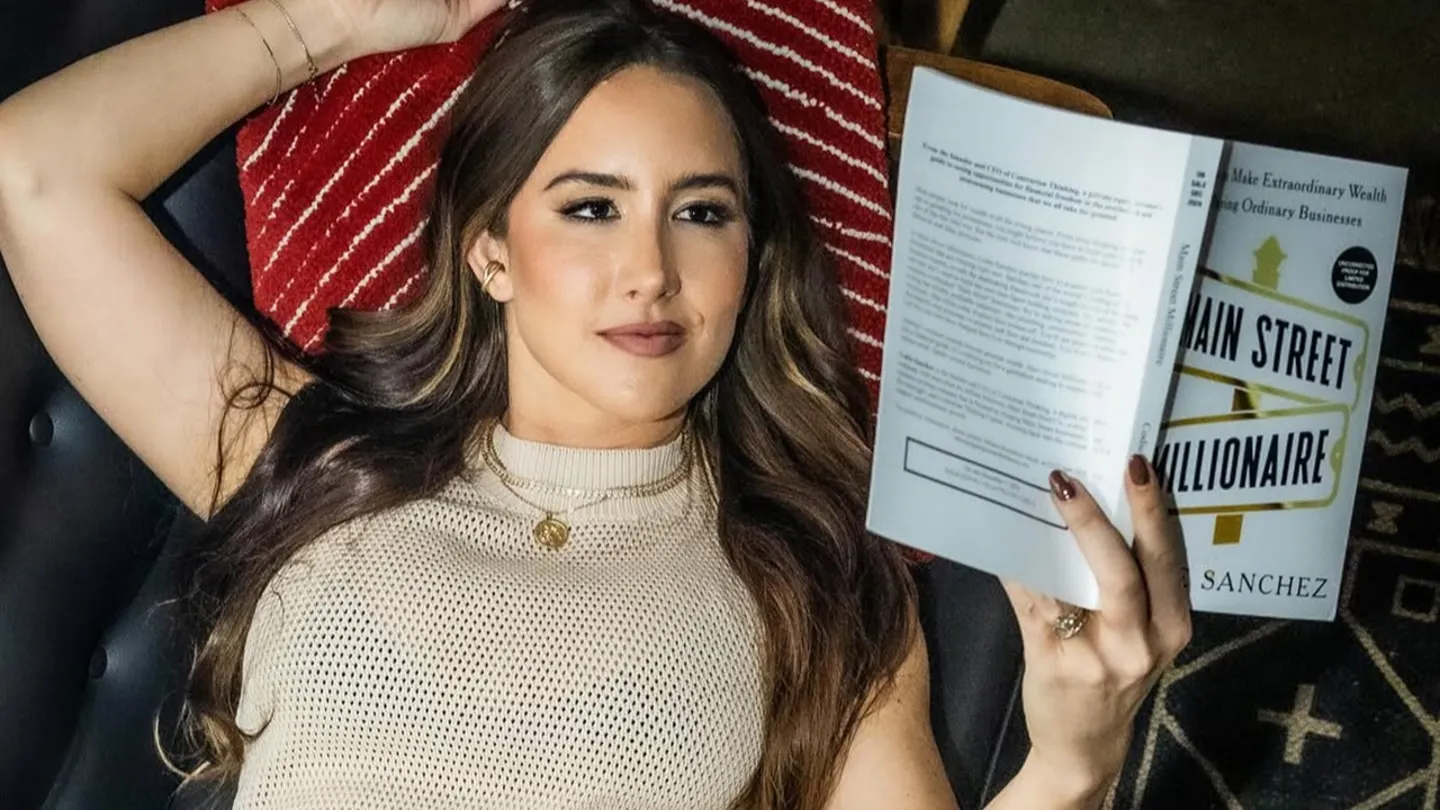

Codie Sanchez had millions of followers, a message people were desperate to hear, and real results to back it up. The first version of her book was headed in the wrong direction.

I remember reading the first draft and thinking: there's a lot of good stuff here. But it took way too long to get into it. The original concept was a "big idea" book. It was even going to be called The Three Waves. The early drafts had three full chapters dedicated to the macro case for buying businesses. The trends, the thesis, the why. It sounded impressive. It was also the kind of book nobody would actually use.

A big idea book (think Bullshit Jobs or Malcolm Gladwell) presents the reader with a new lens on the world. You don't get an outcome from it. You get a perspective shift. That's fine for what it is. But that's not what Codie does. She actually helps people get real, transformative results. So when I read those first three chapters, I told her: these can be three paragraphs in the intro. Just establish it and move on.

It's a common trap. It seems sexier to write a big idea book. Publications highlight those. They win awards. And then nobody reads them, which is why most books don't even sell 1,000 copies. As Codie put it: "If the tagline is 'this book will change the world,' stop it. Try to change the individual, not the world."

So we flipped the whole book. The "why" chapters got compressed. The tactical material moved up front. It became the book Codie originally needed when she was learning acquisitions. A manual you could actually use.

What made the difference was getting specific about who this was actually written for. Not the faceless masses. Real individuals she could picture at the signing table.

The first person Codie pictured was a former coworker. Smart, capable. Everybody knew it. She'd been saying for years she was going to do her own thing. When Codie caught up with her years later, she still hadn't done it. The reason? She'd been told she needed licensing, insurance, a 52-step plan. She got overwhelmed and never started.

Codie wanted to hand that woman a book and say: just read this. You don't have to have the perfect business plan. You don't have to do a SWOT analysis. You don't have to figure out who your first 50 customers are. They're already there. Just start with a little business to buy.

The other person she pictured? Every boss and finance gatekeeper who ever told her she couldn't. She wanted to prove a point: you're not so special in finance. You don't have golden keys nobody else knows about. They could do this just as easily as you can. You just don't want to show them that, because you make more money if they don't.

Every author I've worked with who wrote for the masses instead of real individuals made a worse book for it. No exceptions.

The writing itself has to earn its space. In one of the earliest drafts I read, the book got good when Codie started talking about Lisa Sutton. Tiny, five foot four, former Miss Nevada in sky-high Louis Vuittons, clacking around her dusty mailbox store that prints cash flow. When you meet that character, you can see her. The chapter became exceptional. I told Codie: if we can make more of the book feel like that, it'll be a fantastic book.

Then there's Spencer Scott. A six-nine software engineer who got so fed up with his garbage collector knocking over his bins that he posted a landing page offering to start a garbage company if enough neighbors signed up. He got hundreds of orders. So now on Wednesdays he collects garbage, and the rest of the week he runs SaaS companies. As Codie said: "You've never met a more series of weirdos than people that own small businesses. It's probably why we call them boring. They're the opposite of boring."

The details matter in a different way too. Codie was nervous about sophisticated readers in private equity and hedge funds poking holes in the financials. She went back through every number, built spreadsheets, double-checked terminology. Net income versus net profit matters when millions of followers will find every error.

The cover alone went through 30 versions across three designers before we landed on Pete Garceau's design. Gold foil, high-quality paper, custom graphics throughout the book. We had 150 to 200 versions of those graphics alone. Some of the designers hid easter eggs in theirs. A diamond, a little plant figure. Details you'd only catch if you were paying attention. Because when you're writing about boring businesses, you need the book itself to be anything but boring.

After enough time with the material, you can't tell if it's good anymore.

Codie said it directly: "After writing so much, you can't tell. Sometimes I'm like, I have no idea."

That's where the editor relationship becomes critical. You need a semi-contentious relationship, as it pertains to ideas, with your editor. You can like your editor, but you should be getting in arguments here and there. As Codie described it: "I have to trust that my editor has my best interests at heart and that he wants to see me win. And he has to trust that I want the same thing for him. If that happens, then we're going to win."

Without that trust, authors can talk their editor into thinking a mediocre idea is fine. They're convincing people by nature. That's part of why they have something worth writing about. And then the book suffers for it.

Codie's publisher, Helen, had actually bought a business using Codie's public ideas before she ever signed the book deal. That matters more than most authors realize. Another publisher offered more money. When Codie asked that publisher what their favorite book was, the answer was essentially a polemic about racial guilt. Codie passed on the spot. She went with Helen. The person who had skin in the game and actually believed in the work. When Helen later talked Codie out of a giant launch event because it would make everything about the event instead of the book, it confirmed the decision. That's the sign of a publisher who cares about the brand more than the next quarter.

The book made $1.6 million in its first week.

None of that is what gives the book its real weight, though.

Before finance, before acquisitions, Codie was an investigative journalist on the US-Mexico border. Juarez. The City of Death. She was in her early twenties, covering human trafficking and cartel violence during the peak years. She saw bodies on overpasses. She saw a man stabbed. She walked past hundreds of pink flyers with the faces of missing women. Young, brown-haired, last name Sanchez.

One day it hit her: what's the difference between her and those women on the posters? Not nationality. Not ethnicity. Socioeconomics. Money. If you have money, you can assert your will on the world. If you don't, the world asserts its will on you.

That's what drives the whole thing. As Codie points out, 79% of all millionaires in the US are self-made. But upward mobility is still unfairly distributed toward those who already have some version of wealth. Budgeting won't make meaningful generational change. Stock market investing won't either. You need money to start. Real estate, same thing.

What Codie saw in acquisitions was different: a massive supply of businesses for sale, a tiny demand of people who know how to buy them, and a transaction where nobody has to lose for you to gain. The seller gets a retirement plan. The buyer gets cash flow and equity.

Codie's vision for this book was that someday, somebody hands it to their grandkid and says: this is why the family is where it is today.

Copyright ©

2026, Author.Inc. All rights reserved.